- Cities and buildings

- Fields, plains and deserts

- Forests

- Hills and mountains

- Islands and promontories

- Lands, realms and regions

- Rivers and lakes

- Seas and oceans

|

||||||||

|

Which personality type are you?

Take the Free mydiscprofile Personality Test to discover your core personality and your ideal job.   Which personality type are you? |

|

Dates

Built some time after III 23401

Location

Race

Culture

Other names

Note

In earlier editions of The Lord of the Rings, the name of this gate appears in unhyphenated form as the 'North Gate', while later editions prefer the hyphenated 'North-gate'.

Indexes: About this entry:

|

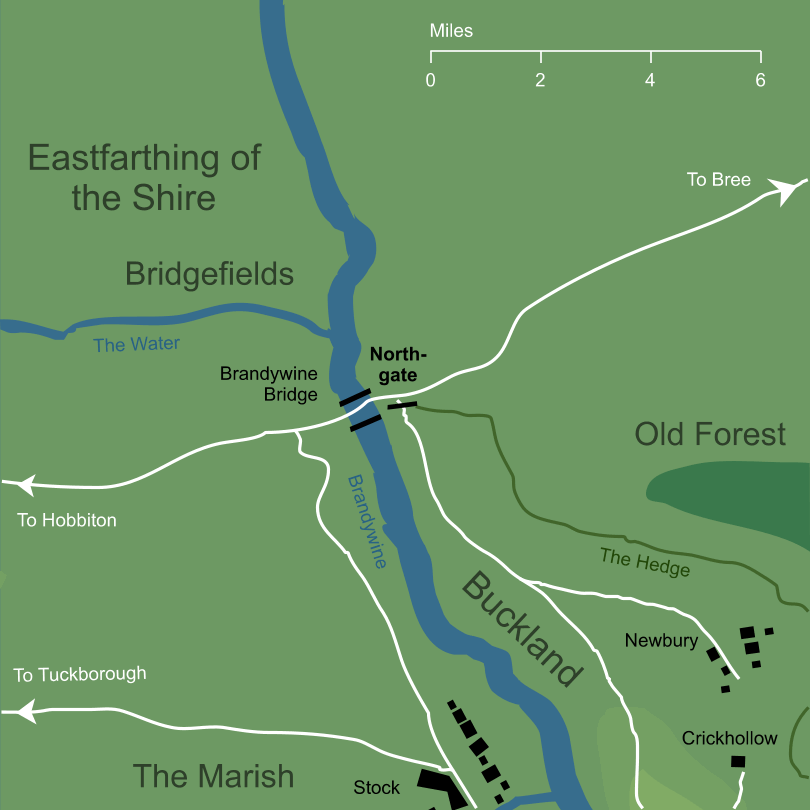

A gate at the northern end of Buckland, the land of the Hobbits that lay east of the Shire across the river they called the Brandywine. Buckland was protected from the dangers of the Old Forest by a great Hedge, and in the north of the land that Hedge turned westward along the East Road to run to the river's edge. Where it met the river, just before the road reached the Brandywine Bridge, the North-gate provided an opening through the Hedge at Buckland's northern extent. For this reason it was sometimes called the Buckland Gate, and its connection to the Hedge (or 'High Hay') also gave it the occasional name of the Hay Gate. It was unusual for the Hobbits of the Shire to show such concern for their borders (the Brandywine Bridge that crossed into the Shire proper had no gate at all, at least until the time of the Chief's takeover in the War of the Ring). Buckland, however, lay on the edge of the dangerous Old Forest, and so its inhabitants not only built the North Gate to protect their lands, but also posted a guard. This guard was not strict, and during the daytime most visitors would be allowed to pass unless they looked particularly suspicious. At night the gate-guards were a great deal more cautious, though they would still allow known inhabitants of Buckland to pass through. As Frodo Baggins and his companions made their journey out of the Shire, they escaped across the Brandywine into Buckland using the Bucklebury Ferry, far to the south of the Gate. The pursuing Black Riders were unable to follow across the river by that route, and instead rode northwards, then across the Brandywine Bridge, and so entered Buckland by the North Gate.2 Coming to the house in Crickhollow where Frodo was supposedly to be found, they discovered him gone. The Riders charged back northward, riding down the guards on the North Gate and setting out along the East Road towards Bree. After this time, Lotho Sackville-Baggins took power in the Shire, and the North Gate was joined by two new gates: one at each end of the Brandywine Bridge. At least some of the guards from the Hay Gate were transferred at this time to guarding the new gates on the Bridge, including the appropriately named Hob Hayward.3 After the fall of the new regime in the Shire, many of the buildings they had raised were torn down again, and this presumably included the gates on the Brandywine Bridge. As for the North Gate itself, the danger of the Old Forest did not end with the passing of Lotho and his ruffians, and, though we're not told its fate for sure, it seems fair to presume that it continued to guard the land of Buckland into the Fourth Age. Notes

See also...Indexes: About this entry:

For acknowledgements and references, see the Disclaimer & Bibliography page. Original content © copyright Mark Fisher 2000, 2017-2018. All rights reserved. For conditions of reuse, see the Site FAQ. Website services kindly sponsored by Discus from Axiom Software Ltd.Discus produces DISC psychometric profiles written in plain language and easily understandable. |